Finding Unexpected Treasure in Lectio Divina

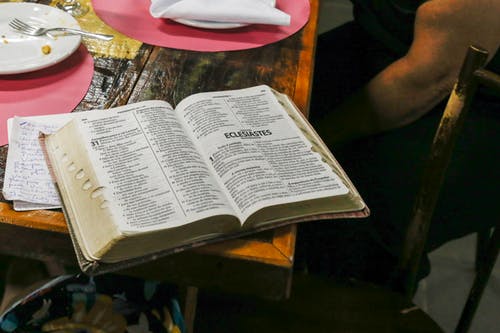

When I was encouraged to attend the School of Lectio Divina, I was drawn to the idea, but I also had some hesitation. I was somewhat familiar with lectio divina (literally “divine reading”) as an ancient practice of praying with scripture, and I had experienced lectio divina in its short form: listening contemplatively to the same scripture passage read aloud three times and paying attention for a particular word or phrase. But I was still unsure whether I wanted to participate.

Others who had attended told me that we were going to be taught the practice of sustained lectio divina. Sustained lectio, unlike the short form I knew, would involve staying with a particular passage for weeks or months at time, returning to it again and again. The practice of sustained lectio is a cornerstone of prayer for Benedictines and of many monastic communities. People often read the same scripture passage every morning as a way to start their day. However, as I considered attending the School of Lectio Divina at the Monastery, I could not escape the reality that I am not a monastic. Five days seemed like a long time to spend with one scripture passage. So, I wondered what would we actually be doing.

Questions and Hesitations

I understood that practicing lectio divina is a way to engage the Bible prayerfully, but the Bible and I have a complicated relationship. My approach to scripture is kind of like Jacob wrestling with the angel. I challenge the text and I expect the text to challenge me. Looking back now, I can appreciate that my way of learning is a lot like sustained lectio--turning the text over and over until some wisdom emerges.

As I considered the School, I knew I wanted to practice engaging the Bible in a more contemplative way, but in a way that also respected my questions and my need to wrestle with the text. I still wasn’t sure if lectio divina would be a meaningful spiritual practice for me, but I decided to try it and see what happened.

Choosing a Text

The first assignment for all participants was to choose a text or, as we were instructed, “to let the text choose you .” The idea of choosing a text felt daunting enough. If I was going to spend five days with one passage, I wanted it be something meaningful. I just wasn’t sure what that text would be. But . . . letting the text choose me?! I wasn’t even sure what that meant.

I wondered about some of my favorite biblical passages--the Burning Bush, the Good Samaritan--until I remembered that I had engaged part of Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians as a part of a workshop. The first line of the passage, But we have this treasure, had stayed with me. After living through a difficult year, I had heard Paul’s phrase as a reminder that even when life is really challenging, there is still beauty to be found. But we have this treasure had become like a mantra for me when things felt hard. So, I decided to engage it further during the School. Maybe that's what they meant by a text choosing me. It seemed like I had started a conversation with the text that I needed to continue. Despite my initial skepticism, by serendipitously appearing at the right time, it felt like my passage had chosen me. I was still skeptical, however, about how I would stay with the same text for five days straight.

Wrestling with the text

As the School progressed, we were encouraged to let the text speak to us in different “voices.” As she guided our group, Kathleen Cahalan suggested that we read our passage in different biblical translations, read commentaries about our passage, and look up the meanings of words that intrigued us. We also spent quite a bit time in silence, which gave me time for walking outside and knitting. Even when I wasn’t actively engaging the text, I felt like it was settling into me, like my unconscious continued to wrestle with the passage even when I was paying attention to other things.

As I turned the text over and over, I resisted some of Paul’s ideas about suffering. And I struggled with how to relate to the persecution and imprisonment that Paul endured. I grappled with these and other challenges in my journal. A few months ago, I drafted another whole blog about these challenges. (The teachers weren't kidding when they said that the text stays with you! I am still wrestling with it.)

Discovering the Power of Small Words

During the five days of the School of Lectio, despite all my intentions to come away with some resolution to my big questions, I was drawn to one short word that begins the first line of the passage: but.

We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed;

perplexed, but not driven to despair;

persecuted, but not forsaken;

struck down, but not destroyed…

Digging up my memory of middle school grammar lessons, I remembered that but is a conjunction. One of the things that conjunctions do is connect two differently true statements together. But tells us that the truth is more complicated than one statement can encompass. But tells us that we need (at least) two clauses to capture more of the story. When I live into conjunctions, my spiritual life is more honest and meaningful. Engaging the buts, yets, ands, and neverthelesses in our lives help us hold multiple truths together at the same time.

Conjunctions Hold Multiple Truths Together

When someone offers too much sentimentality or insists that things always work out for the best, I get uncomfortable. I have witnessed too many situations (in my own life and others’) where things certainly did not work out for the best. When people respond to complicated situations with overly simplified statements, I feel the compelled to add a but, and, yet or nevertheless. Life is beautiful and life is really hard. We want a meaningful spiritual life but we don’t always feel close to God. Conjunctions help us hold complexity and a deeper, broader truth.

We can also miss part of the truth if we generalize in the other direction, focusing only on what is wrong with a situation. I do not say this naively, but I believe that some form of hope is always present. That does not mean that there is a clear path forward or that everything will work out for the best. In many circumstances, finding hope or joy is an act of serious resistance. Honoring the complexity of reality often requires a conjunction . The situation is unjust; nevertheless, we persist. Nevertheless does not deny the injustice, pain, or sorrow. It simply reminds us that the injustice, pain, and sorrow do not tell the full story. Standing alongside that reality is a determination that injustice will not have the last word, even if we don’t know what the future holds. Embracing conjunctions helps us hold space for the pain and for the hope at the same time.

But we have this treasure

Before the School of Lectio began, I had hesitations about spending five days with one text and whether my questions would really be welcome. It turns out that those five days were just the beginning. But we have this treasure and I started a conversation that continues to this day. With two young children at home, I do not engage this text every morning like a monastic, but I have returned to it again and again over the past two years. I had doubts about whether lectio divina would be a meaningful spiritual practice for me, yet it turned out to be a deeply meaningful way for a skeptic to wrestle with a text—because the conversation never ends. My spiritual life seems to flow on like a run-on sentence, as I continue to live into new experiences that help me see the text in new ways. I continue to add clauses to my sentence because there is always more to discover, more to learn. Nevertheless, I keep coming back to this: but we have this treasure.

Learn more about core Benedictine values.

Learn more about core Benedictine values.